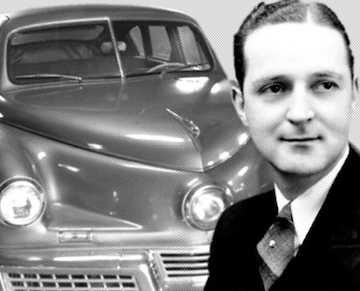

Preston Tucker — The man and his scheme

By William G. Sawyer

Contributing Editor, The Virtual Driver

Photos © Nostalgic Motoring Ltd.

(July 15, 2017) For some, automobile addiction is a fatal disease. It begins innocently enough. An exotic car catches our eye, a friend gives us a spirited ride, or we wander into an auto race that awakens urges we didn’t realize we had. For many, the auto gene lays dormant from birth, waiting to be unleashed by that first whiff of gasoline and tortured gear lube.

Preston Tucker was such a man. Born on a Capac, Mich., peppermint farm in 1903, he was raised in the Detroit suburbs at a time when gasoline-powered frenzy gripped the area. A high school dropout, he worked as an office boy at Cadillac, where he demonstrated out-of-the-box thinking by donning a pair of roller skates to speed up his rounds.

Resurrecting disabled vehicles for profit was an early avocation, but didn’t provide the adrenaline rush his escalating car jones required. Mesmerized by policemen speeding through traffic during hot pursuits, Tucker joined the Lincoln Park, Mich., police force to get in on the fun. That came to naught one frosty day when he was pulled off the motorized detail after taking a blowtorch to the firewall of his assigned vehicle in order to allow engine heat to warm his shivering body.

Tucker hopped from job to job, running a gas station, working on the Ford assembly line, and selling cars, to name a few. Sales proved to be his forte. He worked his way up the ladder, becoming general sales manager of a dealership in Memphis, Tenn., before finding his way to Buffalo, NY where he became the regional sales manager for the faltering Pierce Arrow.

The Indianapolis 500 represented the pinnacle of motorized euphoria in the thirties, and Preston Tucker was drawn to it like an addict to a simmering spoonful of heroin. Unsatisfied by his annual treks to the Brickyard, Tucker relocated to Indianapolis where he took a job as fleet manager for a beer distributor to be closer to the action.

His unbridled enthusiasm, technical acumen, far-reaching vision, and persuasive nature ingratiated him to the racing folk in town. He eventually met and charmed Harry Miller, one of the most talented race engineers America ever produced. Fresh out of bankruptcy court, Miller fell under Tucker’s spell and soon they founded Miller & Tucker to build an armada of Miller-Ford racers for the Dearborn-based car maker.

The project was a rush job, receiving approval and funding late in the game, and resulted in the poorly positioned steering gears overheating. The resultant lack of steering forced all of the Miller-Ford’s out of the race, although subsequent owners found reasonable success after rectifying the problem.

Soon thereafter, the changing political scene in Europe turned Tucker’s fertile imagination to the war effort. He developed an armored combat car powered by a Miller-modified Packard V-12 that never reached volume production, and designed an electrically powered gun turret — the Tucker Turret — that some experts say wasn’t as successful as folklore portrays it to be.

Too optimistic to be put off by failure, Tucker turned his attention to the skies. He established the Tucker Aviation Corporation in the machine shop behind his Ypsilanti, Mich., home. There he developed the Tucker XP-57, nicknamed The Peashooter, a tube-frame, aluminum and plywood fighter plane powered by a Harry Miller-designed straight eight engine.

The Army Air Corps ordered a prototype that never saw the light of day due to funding difficulties. The company was sold in 1942 to Higgins Industries, manufacturer of Liberty ships, PT Boats, and landing craft. Tucker moved to Louisiana to assume leadership of the Higgins-Tucker Aviation Division, but a falling out with company patriarch Andrew Jackson Higgins found Tucker out of a job and heading back to Michigan the following year. One can only imagine the nuance behind Higgin’s comment when he referred to Tucker as “the greatest salesman in the world”.

If you see a pattern developing, you’re right. Tucker was a visionary who knew a great opportunity when he saw one, but he moved too fast for the pesky details that make the difference between success and failure to catch up. If that hadn’t been apparent before, it became all too clear when he embarked on his most famous venture of all, The Tucker 48.

If you see a pattern developing, you’re right. Tucker was a visionary who knew a great opportunity when he saw one, but he moved too fast for the pesky details that make the difference between success and failure to catch up. If that hadn’t been apparent before, it became all too clear when he embarked on his most famous venture of all, The Tucker 48.

The end of hostilities created the ideal environment for a man with big ideas. After nearly two decades of sacrifice during the Great Depression and World War II, returning G.I.s devoted their ingenuity and can-do attitude toward creating an economic boom that eventually lifted the remainder of the free world along with it. Demand for new cars soared, but the rehashed metal the established car makers rushed into production left many Americans cold.

Enter Preston Tucker with a spellbinding tale of a new car brimming with technology and innovation. The December 1946 issue of Science Illustrated magazine broke the story with a feature on what was then called the Tucker Torpedo. The article featured a photograph of a 1/8th scale model of the concept positioned to look as if it was a real, production-ready vehicle. Tucker added fuel to the fire in March, 1947 with full-page ads in newspapers throughout the country proclaimed that the new car was the result of 15 years of testing and development. True to form, “testing and development” was a euphemism for Tucker’s day dreams about the car he longed to create — a fact that became apparent as the project progressed.

Even the body design was in flux. Originally penned by George S. Lawson, Tucker hired Alex Tremulis to refine it, and then brought in the New York design firm of J. Gordon Lippincott to further develop the final look. If that wasn’t enough, the engine Tucker envisioned didn’t work out, at least three separate transmissions were tried, and he went through several suspension configurations.

Behind the smoke and mirrors was a chrysalis attempting to grow into a car unlike anything else the world had seen. It was so unique you wouldn’t be blamed if you thought a flying saucer deposited it at the foot of Woodward and Jefferson in downtown Detroit. Like an alien, it had three eyes, thanks to a center-mounted headlamp that turned with the front wheels.

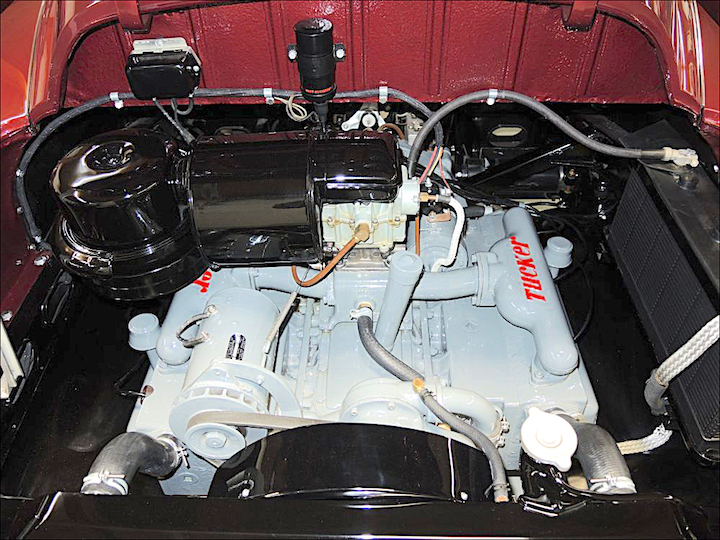

The engine was in the rear for better traction, and it possessed a continuously variable transmission with one forward and one reverse gear at a time when three-speed manuals were the norm. That drivetrain was mounted on a sub-frame attached with a total of six bolts so the whole thing could be swapped out if necessary.

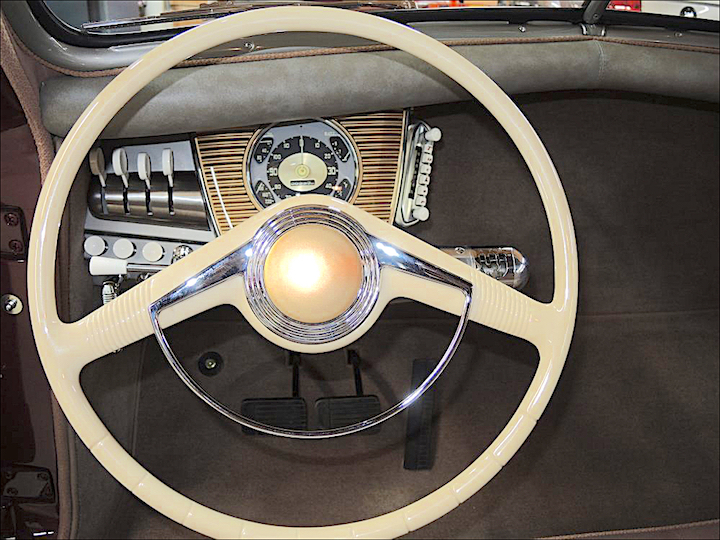

Safety was a prime consideration. The dash was padded, with an instrument panel and controls situated in front of the driver. In fact, there was little more than a padded bar ahead of the front seat passenger, creating a crash chamber where occupants could crouch for protection in case of an accident. That sounds laughable in these days of safety belts and air bags, but Tucker deserves credit for attempting a solution, for moving knobs and switches behind the steering wheel where they couldn’t harm the passenger, and adding padding to the top of the instrument panel.

Space was created in front of the passengers for a "crash box" into which they could jump when a crash was imminent

Some surmise Tucker also had a collapsible steering column under development. Another safety feature was a pop-out windshield credited with helping save the life of a driver involved in a high speed testing incident during reliability runs at the home of the Indy 500, Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

However, it takes more than hype and advertising to create a car company. It takes money, lots of it. To solve that problem Tucker sold stock to the public, hawked 2,000 dealerships for $7,500 to as much as $30,000 each, and created a Tucker Accessories Program that promised a guaranteed spot in line to those who shelled out in advance for seat covers, radios, and luggage. This much needed capital made it possible to obtain the largest factory in the world, 475 acres of manufacturing capacity in Chicago that now houses a Tootsie Roll factory and a shopping mall.

Among those investors was a flautist with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra who moonlighted on The Ford Sunday Evening Hour, a concert music radio show sponsored by the Ford Motor Company. Although he lost $5,000 on his investment in Tucker stock he never regretted the decision. In fact, he regaled his children with tales of the man who dared to thumb his nose at the establishment and follow his dream. One of his sons took that story to heart, moving to Hollywood where he became a legendary director. The son turned his father’s stories into a movie starring Jeff Bridges as the irrepressible genius stifled by the establishment. It wasn’t a success but, like the Tucker car, Francis Ford Coppola’s movie Tucker, The Man and His Dream became a cult favorite. Carmine Coppola never received the Tucker he ordered new, but his son Francis now owns two of them.

The instrument panel grouped all controls in front of the driver with aircraft-inspired switches and levers

While on the hunt for working capital, Tucker hustled to solve problems with his design. He spent $1.8 million to buy Air Cooled Engines, a manufacturer of aviation engines that spun off from the Franklin Automobile Company and still sold its products under the Franklin name. In order to ensure availability of the Franklin O-335 for his autos, Tucker cancelled all existing aviation contracts, a problem since the company held a 65% market share.

Meanwhile, Drew Pearson, the syndicated newspaper columnist, caught wind of the fact that the Tucker prototype was unable to reverse. He ran with the rumor and it became urban legend, even though the problem was limited solely to the initial Tucker prototype.

Along the way Tucker executives came and went, causing consternation in the ranks, the Feds took umbrage at Tucker’s innovative funding schemes, and some — including Coppola — say Detroit pressured the government to shut Tucker down before he could do them harm. Investigations ensued, bad publicity multiplied, and frustrated dealers clamored for Tucker to produce cars or repay their franchise fees.

Despite the issues plaguing the project, over 3,000 spectators attended the official debut of the Tucker 48 (the Torpedo moniker never made it to production). The suspension arms snapped due to the prototype’s weight, and the engine was kept running throughout the ceremony so the public couldn’t witness how difficult it was to get it to fire. Tucker managed to manufacture 51 Tucker 48s, including the prototype — now with revised suspension and the Franklin O-335 engine — -before the company folded. Today they’re spread across the globe, residing in Melbourne, Australia, Brazil, and the Toyota Automobile Museum in Japan, as well as throughout the U.S.

Our reference vehicle, Tucker #46, is available from Nostalgic Motoring Ltd. in Auburn Hills, Mich., for an asking price of $2.1 million. Nostalgic’s owner, Mark Lieberman, is a recognized Tucker guru who has owned and restored a number of these cars. He also has another Tucker, built on a factory test chassis and finished using genuine Tucker parts from various sources, for about half the price. 2015 saw it take its class at the Concours of America at St. John’s in Plymouth, Michi. Not bad for a “continuation”.

Like an artist whose talent isn’t recognized until after his death, the Tucker 48 has attained a place in automotive folklore few can rival. Arguments swirl among car guys and conspiracy theorists about the true merits of the vehicle and the circumstances surrounding its demise, but none of that really matters any longer.

The automotive landscape is richer because Preston Tucker was willing to sacrifice it all to realize his dream.