Perrymobile was a rationless World War II era alternative car

By Robert D. Cunningham

The Old Motor

(January 26, 2021) For a time in 1944, when World War II gasoline rations were just two gallons per week, many automobile owners drained the precious fluid from their tanks, filled the engine cylinders with oil, and put their cars up on blocks. However, a few fortunate owners of obsolete electric-powered and steam-powered cars pressed their relics back into service. And one clever Los Angeles inventor demonstrated what he claimed was a greatly improved version of the steam-powered motor that any mechanic.

“My ration-free Perrymobile is the liquid-and-air car of tomorrow,” exclaimed Frank R. Perry, a former Air Service Command technician. Perry had designed and built a small, 30-horsepower, four-cylinder, two-cycle engine powered by compressed air and a quart of a mysterious, green liquid. No noise, smoke or smell. And its operation was smooth.

“With your eyes closed, it’s is impossible to tell when the car starts moving,” Perry claimed. “There are no terrifically high engine speeds, internal explosions or carbon formations like those that wear out the internal combustion motor. The Perry Motor gives you full power at any speed. You can drive away from a cold start in a few seconds. You don’t depend on momentum for speed or power to take the hills. You can stop a Perrymobile on the steepest hill and start again with full power and speed at the touch of the throttle. Drive a gasoline automobile in gear against a stone wall and the wheels will stop. Try it with a Perrymobile and the wheels will continue to revolve.”

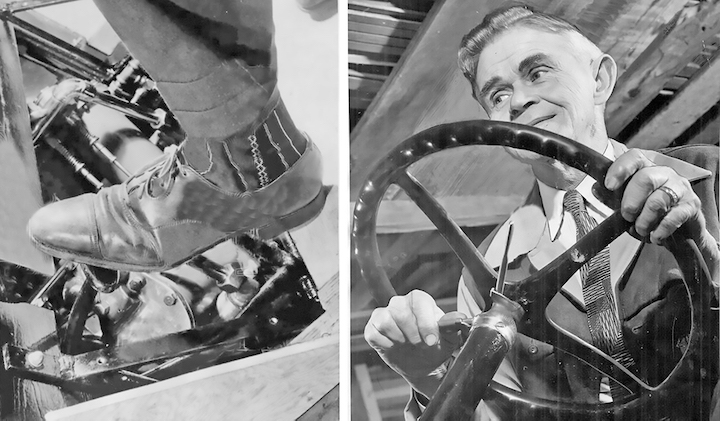

Perry and his wife take a drive

The Perrymobile’s 140-pound Perry Motor resided under the hood of an old Model A Ford from which Perry had removed most of the body. The engine was nestled between a plywood firewall and a large, square boiler. (Naturally, folks wanted to get a good look at his miracle motor, so Perry soon replaced the firewall with a Plexiglas dashboard so that all parts could be readily inspected.)

The operating system included a compressed air tank to help start and operate the motor. A cylindrical tank mounted behind the seat held 10 gallons of butane, which was used to heat and expand the air and vaporize the liquid. To start his contraption, Perry opened a fuel valve under the hood to release butane to the burners. Then he hopped into the driver’s seat and pulled down the right-hand throttle lever on the steering column. Compressed air instantly moved from the air tank into the cylinders and the car began to move. A single floor pedal operated the brakes.

Within a minute or two after starting, the secret liquid, similar to refrigerant, vaporized at a temperature of just 150 degrees Fahrenheit. When Perry turned off the air pressure the pressurized vapors were forced from the boiler into the engine, pushing the cylinders down and exhausting it into the radiator to be condensed and recovered as green liquid. All the while, a small belt-driven pump restored compressed air to the tank. Another lever changed the position of the cams for reversing the motor.

Perry regulated the amount of butane flowing from a 10-gallon tank behind the seat to the burners with a simple valve wheel

“On just two gallons of butane I can cruise for 17 hours at the national speed limit of 35 miles per hour,” Perry said. His motor turned only 800 revolutions per minute at speeds of 80 miles per hour. So, he claimed, his engine worked only 40 percent as hard as the traditional internal combustion engine. Without other “bothersome parts” such as a clutch, carburetor, spark plugs, distributor, coils, battery, fan, gear box and self-starter, the car was nearly maintenance-free. Perry estimated that less than one quart of lubricating oil was required per year.

It had cost Perry about $400 to build his lightweight automobile, but he said it should sell for much less if it got into mass production, assembled on used chassis—about $250. His Perry Motor was constructed of salvaged parts, which may have included a Model A Ford crankshaft, Packard pistons, Dodge valves, and Marmon rods. “I am convinced that this is the type of power plant which will operate the automobile of the future,” he proclaimed. He believed his air-vapor engine could also be used on helicopters and boats as well as automobiles.

Perry’s contraption was featured in newspapers and magazines all over the world. Bing Crosby and other celebrities were eager to invest. Henry J. Kaiser, the wealthy construction and shipbuilding tycoon, was most interested in the postwar manufacture of a refined Perrymobile. Kaiser entered into negotiations with the Perrymobile Company of 663 W. Jefferson Blvd., in Los Angeles. But Frank Perry did not trust the powerful businessman. “There’s no need to mass-produce the Perrymobile,” he said. “Any good mechanic can duplicate its mechanical features without spending a lot of money, and I can earn good profits simply by selling plans and non-exclusive licenses, which will enable other men to build their own autos.”

A foot pedal released vapor from the air tank, while the right control on the steering column regulated pressure and the left control reversed the motor

Instead, Perry partnered with A.J. Brauer, a retired shoe manufacturer from St. Louis, Mo., to establish the Perry-Brauer Motor Company. On Feb. 1, 1945, the firm signed a six-month lease on exhibit space in the local Shrine auditorium. There, Perry explained the science behind his vehicle and a motion picture showed the car in practical use.

“For just $25, we will sell you a set of easily understood blueprints and specifications,” Perry said. “And you’ll have a license to build, or have built, one power plant for your own use.” The cover of his new brochure pictured a sleek, slab-sided, streamlined “postwar Perrymobile,” but it was actually a concept illustrated by stylist George Walker, a Detroit futurist who envisioned plastic postwar automobiles to sell in the range of $300 – $400, that they simply pasted onto their layout prior to printing.

Perry was deluged with up to 500 letters daily requesting information and copies of his blueprints. “We are not encouraging correspondence,” Perry’s staff wrote in response. “We are flooded with mail from all parts of the world.” One American soldier urged Perry to rush the plans to his base on a Pacific island where parts from captured Japanese war planes would be used to build a Perrymobile.

Automotive industry experts weighed in as news of Perry’s invention circulated. Many said Perry’s fragile engine was not sufficiently engineered to stand up under constant air pressure. They said it would bog down on steep hills, and the boiler was a fire hazard. As the scrutiny intensified, inquiries dropped to just a few each week, and the Perrymobile exhibition closed early. Afterwards, Frank R. Perry quietly turned his attention to the improvement of deep-sea fishing equipment.

Robert D. (Bob) Cunningham is a commercial illustrator and author of several automotive history books.