Lost to fire, Ford’s Rotunda destroyed 60 years ago

By Jeff Peek

Hagerty

(November 12, 2022) Ford called it the “Show Place of the Automotive Industry,” and even a title that brazen may have understated the widespread appeal of the Rotunda. By the early 1960s, Ford’s futuristic Rotunda was not only the most popular automotive-related tourist destination in the United States, it was the fifth-most visited attraction overall, seen by more people than the Statue of Liberty, the Washington Monument, and Yellowstone National Park.

Never heard of the Ford Rotunda? You’re forgiven. It’s been six decades since the building was lost forever on Nov. 9, 1962.

On that pleasant Michigan afternoon, workers were applied waterproofing sealant to the roof when a heater ignited the fumes. The beloved structure was consumed in a flash of flames. Less than an hour later, it was destroyed. While the Ford Rotunda is now relegated to photos and faded memories, those who remember it do so fondly, not just for its endless automotive displays and history lessons, but for its massive Christmas makeover each year.

On that pleasant Michigan afternoon, workers were applied waterproofing sealant to the roof when a heater ignited the fumes. The beloved structure was consumed in a flash of flames. Less than an hour later, it was destroyed. While the Ford Rotunda is now relegated to photos and faded memories, those who remember it do so fondly, not just for its endless automotive displays and history lessons, but for its massive Christmas makeover each year.

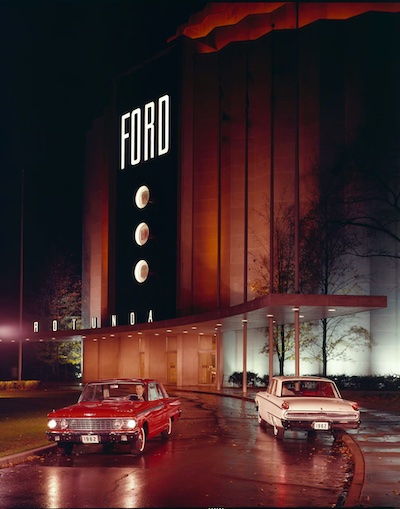

“Over the years, the Rotunda acquired a special personality all its own,” Detroit Free Press columnist Mark Beltaire wrote in 1962. “It was known and recognized by people who had never been inside. They were aware of the Rotunda, especially at night, even while driving many miles away.”

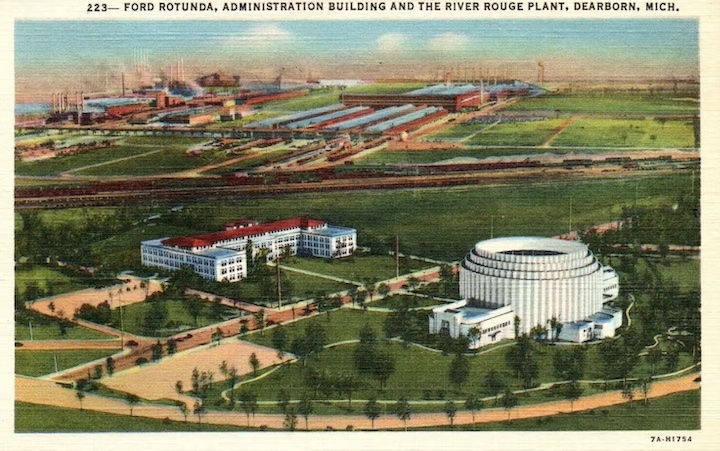

Built by legendary Detroit architect Albert Kahn as the centerpiece of Ford’s exhibit in the 1933–34 Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago, the Rotunda stood 10 stories tall and resembled gears stacked atop one another. Kahn had already designed a number of iconic Motor City buildings, including the Packard plant and Ford’s River Rouge plant, but this one was unlike any he had ever created. World’s Fair attendees flocked to it.

Rotunda under construction in mid 30s

Henry Ford so loved the Rotunda that at the end of the fair, he wanted to add it to his collection of historic buildings at Greenfield Village, just a short drive from the Rouge, and use it to display historical advancements in industrial engineering. However, Edsel Ford convinced his father that it would be better used as a visitor center and starting point for the company’s popular Rouge plant tours. So, the huge structure was disassembled and shipped to Dearborn, where it was reassembled in 18 months—with slight design changes made by Kahn—on a 13.5-acre site across from the Ford Administration Building on Schaefer Road.

The building’s 1,000-ton steel frame was covered in 114,000 square feet of Indiana limestone, and its expansive interior featured murals showing the River Rouge assembly line. Ford’s newest cars were on display. Outside, the Rotunda also featured the original “Roads of the World” exhibition from the World’s Fair. (Later, two wings were added, one for the Ford Motor Company Archives and the other for a theater. In 1952, an 18,000-pound dome was added over the courtyard; it was the first real-world application of inventor R. Buckminster Fuller’s lightweight geodesic dome.)

Automobiles on display in 1936

On May 14, 1936, the relocated Rotunda opened its doors to the public. It was an immediate hit, just as it had been at the World’s Fair. Ford says the Rotunda welcomed more than 61,000 visitors the first week and that during the 26 years that followed—including four during World War II in which the building was shuttered—more than 13 million people visited. (Some sources put that number between 16 and 18 million.)

Beginning in late November 1953, following an extensive restoration timed to celebrate the company’s 50th anniversary, Ford hosted its first Christmas Fantasy extravaganza. Growing in size and complexity each year, the annual transformation became the Rotunda’s biggest drawing card, and it’s no wonder.

Christmas Fantasy 1955

Its features included a 35-foot-tall tree with thousands of lights, Santa’s workshop with a crew of animatronic elves, a life-size Nativity that the National Council of Churches called the country’s “largest and finest,” and a wall display of more than 2,000 dolls that were dressed by members of the Ford Girls’ Club and later given to underprivileged children. The overall theme changed each year—featuring everything from storybook characters to circus animals—but the pinnacle of every Christmas Fantasy was the opportunity to visit Santa Claus himself … after standing in a long line of children and parents, of course.

On the day of the fire, workers were busy erecting the indoor displays in time for the festivities, while workers outside were waterproofing the dome panels in anticipation of winter weather.

Author David Maraniss described the scene in Once in a Great City, his 2015 book about Detroit in the 1960s:

The quintessentially American harmonic convergence of religiosity and commercialism was expected to attract more than three-quarter of a million visitors before the season was out, and for a generation of children it would provide a lifetime memory—walking past the live reindeer Donner and Blitzen, up the long incline toward a merry band of hardworking elves, and finally reaching Santa Claus and his commodious lamp.

An elementary school class had just left the Rotunda when, about 1 p.m., a worker reported flames on the roof. A security guard quickly called the fire department and evacuated the building, but by the time firefighters arrived, the roof was fully ablaze. Soon the steel frame began to buckle, and at 1:56 p.m., firefighters were ordered away from the building as the walls began to crumble.

An elementary school class had just left the Rotunda when, about 1 p.m., a worker reported flames on the roof. A security guard quickly called the fire department and evacuated the building, but by the time firefighters arrived, the roof was fully ablaze. Soon the steel frame began to buckle, and at 1:56 p.m., firefighters were ordered away from the building as the walls began to crumble.

In Once in a Great City, a witness said the building’s collapse looked “as though you had stacked dominos and pushed them over.” The roof crashed into the Christmas displays below, and flames shot 50 feet into the sky before firefighters could control them.

The Ford Rotunda, which earlier in the day was being prepared for a highly anticipated Christmas celebration, now sat in smoldering ruins. The spirits of thousands of past and future visitors sank.

Ford considered rebuilding the Rotunda, but the price tag was an astounding $15 million, the equivalent of more than $147M today. What remained of the building was razed, along with the theatre, which had also been destroyed. (On the bright side, the Ford Motor Company Archives survived.)

The site sat vacant for nearly 40 years until the Henry Ford College Michigan Technical Education Center (M-TEC) opened there in 2000.

The Rotunda, a uniquely designed building that was once the fifth-most visited tourist attraction in the U.S.—behind only Niagara Falls, Smokey Mountain National Park, the Smithsonian, and the Lincoln Memorial—is now just a footnote in automotive history. But to those who saw it in person, especially at Christmas or illuminated at night, it was much more than that.

“Tears for a building?” Beltaire asked in his Free Press column, written after the fire. “Of course, and many [tears] when such as the Ford Rotunda dies.”

Photos: Henry Ford Collection