Crosley Hotshot — Serious contender too few took seriously

1950 Crosley Hotshot

By Robert D. Cunningham

The Old Motor

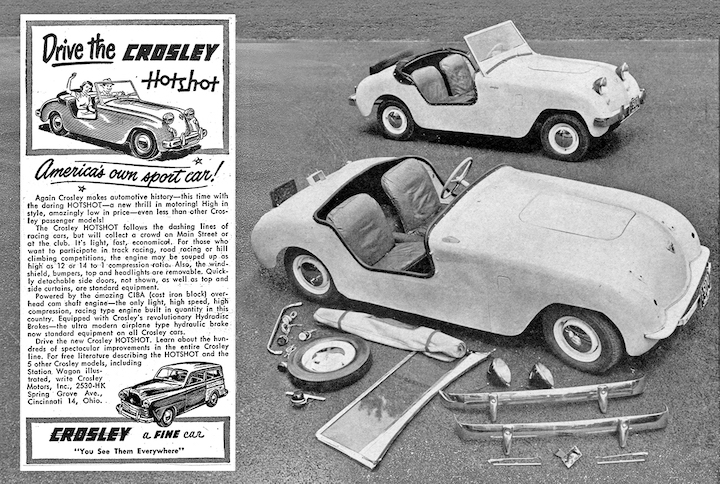

(August 22, 2021) Powel Crosley, Jr. introduced his two-cylinder roller skate of a car in 1939, followed by slightly larger postwar offerings in 1946. All body styles were strictly practical until he unveiled his exciting new Hotshot on July 13, 1949. “America’s first true postwar sports car” was a bare-bones street racer. Being equipped with few frills allowed dealers to deliver the roadster for as little as $316 down and $7.64 per week, and at only $849, the Hotshot was the least expensive production car in America that year.

It was designed by Sundberg & Ferar to meet Powel Crosley’s specifications, and Crosley had Lincoln Zephyr stylist John Tjaarda layout the dashboard, which was not used on the production car. Depending on one’s economic background, the roadster was either a little racer or a big roller skate. It ended up being only 37 inches at the rear of the cowl and has seven inches of clearance. Easily stripped of windshield, bumpers, lights, spare tire, and other unnecessary items, the Hotshot, in racing form, weighed in at just 991 pounds.

A California Crosley driver proudly displays a tiny loving cup won at the wheel of his four-cylinder 1950 Hotshot.

The roadster body was fabricated from six basic panels welded together that form a sturdy body shell. It may have been the first production sports car to eliminate the grille, and cooling air was ducted to the radiator by an air scoop mounted under the front bumper. There were no hinged panels, such as doors, trunk lid, or hood. The 26.5 horsepower engine was accessible only by unlocking and lifting off a small, rectangular cover in the center of the front deck. It was an appealing package with styling similar to the bug-eyed Austin Healey Sprite, built a decade later.

The exciting new Hotshot attracted attention at local race tracks. Its unique suspension system consisted of conventional semi-elliptic springs up front and a torque tube located rear axle with coil springs on top of single leaves at the rear, providing a soft but stable ride. With increased compression and special 10:1 pistons, the pussycat Crosley became a tiger with top speeds approaching 85 miles per hour.

Aftermarket parts supplier Mick Brajevich supplied Crosley owners with cast aluminum finned cam covers and oil pans, dual carb manifolds, headers, and other lightweight add-ons that could nearly double the horsepower and raise the top speed to 100 miles per hour. Fritz Feierabend drove car #2 to victory in the 1950 Grand Prix de la Suisse Occidentale for sports cars up to 750cc displacement. Despite the necessity for slowing down to navigate dangerous road curves, Feierabend averaged 51 mph. Oviedo Bernasconi’s Hotshot, which used an Ital-Mechanica compressor, placed second.

Stock 1949 hotshot was easily stripped of extraneous do-dads to create a potent, lightweight racer for under $1,000.

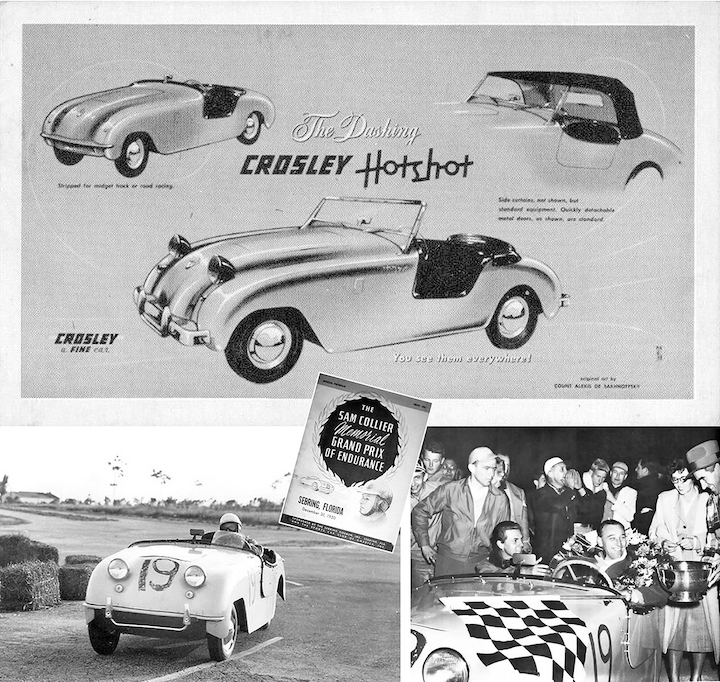

Later that year, on New Year’s Eve, drivers Fritz Koster and Ralph Deshon drove a Hotshot to victory in a six-hour handicapped road race, the first-ever held at the Sebring, Florida, airport. The Crosley’s participation was a snap decision. When Vic Sharpe arrived from Tampa in his Hotshot to deliver tires for Tommy Cole’s Cadillac-powered Allard, Sports Car Club of America members Koster and Deshon realized that the Crosley’s small engine displacement could be a real advantage.

The event was run under rules devised by France’s Automobile Club de l’Quest, organizers of the famous Le Mans Grand Prix d’endurance. Winners would be determined only after applying a horsepower-to-distance mathematical formula, thereby making the contest fair to every participant, regardless of how much money they spent on development. Koster and Deshon quickly convinced Sharpe to loan them his car. Immediately they removed the hubcaps and windshield, bolted a short piece of Plexiglas on the edge of the cowl, and registered for the race.

A bone stock Crosley Hotshot rolled from the street to the track, and on to Victory Lane in the inaugural Sebring endurance event in 1950.

When the starter’s whistle blew, Koster and Deshon ran across the track with the other drivers and slid into the cockpit. Twenty-eight engines roared to life, and the race was underway. Koster quickly shifted the tiny transmission into high gear and kept it there throughout the race. Running at a constant 7,500 rpm, the Hotshot screamed like a chain saw on the straightaways and was driven wildly into the corners. In the end, a Ferrari logged the highest distance, having lapped the 3.5-mile course 166 times. The Crosley completed just 89 laps. However, after applying the handicapping formula, the only American car to compete emerged in the first place. Koster and Deshon rolled into the winner’s circle to receive a floral laurel, trophy, and accolades from seasoned racers.

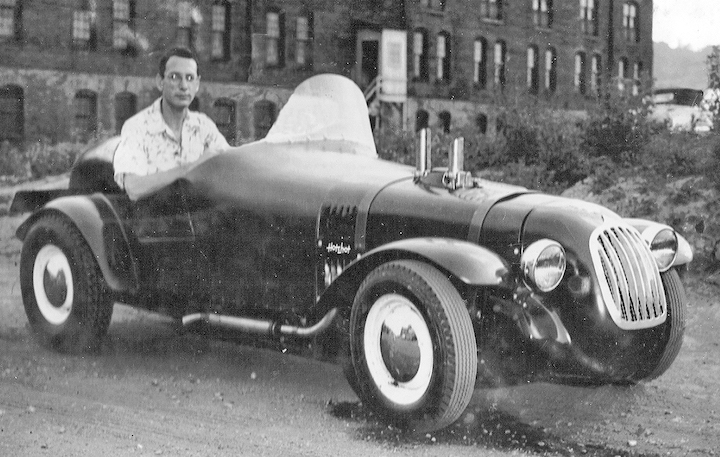

Meanwhile, nonparticipant Phil Stiles periodically lapped the track to remove debris, including parts that had vibrated loose from the race cars. He was impressed by how well the winning Crosley held together, and his wife urged him to ask Powel Crosley to build a true racer for Styles to drive in the French Le Mans. Crosley liked the idea and engaged Floyd “Pop” Dreyer in Indianapolis to create a sleek, slender, fat-fendered racer.

Dolph Vilardi drove a yellow 1950 Hotshot #4 with optional detachable doors and aftermarket Braje grille to finish 1st in Class H Modified at Watkins Glen.

For the Crosley Hotshot LeMans Special, Dreyer acquired speed equipment from various sources, including Braje, Harmon & Collins, Iskenderian, Sun, and Bell Auto Parts, to boost horsepower from 26.5 to 42. Holes were punched in the hood to facilitate two chrome-plated intake stacks that allowed the down-draft carburetors to breathe. Powel Crosley was so enthused with the project that his boat trailer was modified to carry the newborn race car to the Pennsylvania Turnpike, where the vehicle was unloaded near Harrisburg, and George Schrafft climbed aboard. The Hotshot Special then roared off down the Turnpike in an attempt to break in the engine before being shipped to France aboard the S.S. Liberte.

Upon arrival at race headquarters, the crew discovered that the headlights were dim, so a French Marchal generator was installed. Road tests also revealed that a larger capacity gasoline tank was needed. Generous assistance came from the famous Cunningham racing team. The Hotshot LeMans Special performed well on race day, averaging 73 miles per hour on initial laps with plenty of power to spare. When cornering, the Crosley actually passed some competitors, including a Talbot, one of which won the previous year’s event.

Phil Stiles was pleased and a bit smug with the car’s surprising performance until the generator seized and a fire broke out in the cockpit. Choking on the smoke and unable to see, Stiles veered into the pits where the crew awaited with fire extinguishers. The bearings in the replacement generator had failed. Because the fan belt also powered the water pump, cooling water could not circulate from the radiator into the engine. Stiles feverishly snipped away at the burnt wires and rerouted the water hoses to bypass the pump. He would rely on the old thermosyphon cooling method that had worked so well for American Austin and Bantam. In short order, the Crosley was back on the track. Unfortunately, the radiator was too small to cool the water, and the engine overheated. The Crosley Hotshot LeMans Special was withdrawn after completing only 40 laps.

Legendary race car builder Floyd “Pop” Dreyer built this custom Hotshot for Powel Crosley, Jr.

Unfortunately, Powel Crosley’s promising premiere on the racing scene came too little, too late. He had invested heavily in his dream of building an auto manufacturing empire — $3.2 million of his own money, countless hours, and the sacrifice of his family life. But his best intentions could not win over a public that had no interest in tiny sports and economy cars.

“The people in this country who go in for keeping up with the Joneses will buy a secondhand, beaten-up wreck rather than a brand-new small Crosley — if the big car still looks impressive to them,” he lamented. Crosley reluctantly closed the company, and production officially ended on July 16, 1952.

Robert D. (Bob) Cunningham is a commercial illustrator and author of several automotive history books.